A Heian-era mansion stands abandoned, its foundations resting on the bones of a bride…

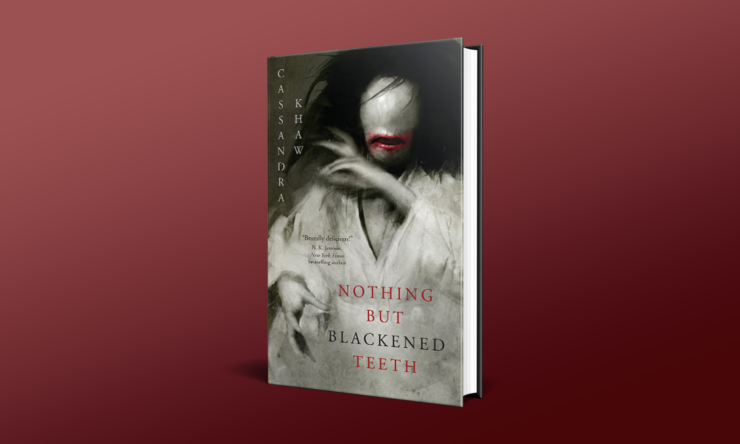

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Cassandra Khaw’s Nothing But Blackened Teeth, a gorgeously creepy haunted house tale steeped in Japanese folklore—publishing October 19th with Tor Nightfire. Read the first chapter below, and check back for additional excerpts this week!

A Heian-era mansion stands abandoned, its foundations resting on the bones of a bride and its walls packed with the remains of the girls sacrificed to keep her company.

It’s the perfect venue for a group of thrill-seeking friends, brought back together to celebrate a wedding.

A night of food, drinks, and games quickly spirals into a nightmare as secrets get dragged out and relationships are tested.

But the house has secrets too. Lurking in the shadows is the ghost bride with a black smile and a hungry heart.

And she gets lonely down there in the dirt.

Effortlessly turning the classic haunted house story on its head, Nothing But Blackened Teeth is a sharp and devastating exploration of grief, the parasitic nature of relationships, and the consequences of our actions.

Chapter 1

“How the fuck are you this rich?” I took in the old vestibule, the wood ceiling that domed our heads. Time etched itself into the shape and stretch of the Heian mansion, its presence apparent in even the texture of the crumbling dark. It felt profane to see the place like this: without curators to chaperone us, no one to say do not touch and be careful, this was old before the word for such things existed.

That Phillip could finance its desecration—lock, stock, no question—and do so without self-reproach was symptomatic of our fundamental differences. He shrugged, smile cocked like the sure thing that was his whole life.

“I’m— Come on, it’s a wedding gift. They’re supposed to be extravagant.”

“Extravagant is matching Rolex watches. Extravagant”—I slowed down for effect, taking time between each syllable—“is a honeymoon trip to Hawaii. This, on the other hand, is… This is beyond absurd, dude. You flew us all to Japan. First class. And then rented the fucking imperial palace or—”

“It’s not a palace! It’s just a mansion. And I didn’t rent the building, per se. Just got us permits to spend a few nights here.”

“Oh. Like that makes this any less ridiculous.”

Buy the Book

Nothing But Blackened Teeth

“Ssh. Stop, stop, stop. Don’t finish. I get it, I get it.”

Phillip dropped his suitcases at the door and palmed the back of his neck, looking sheepish. His varsity jacket, still perfectly fitted to his broad quarterback frame, blazed indigo and yellow where it caught the sun. In the dusk, the letters of his name were gilt and glory and good stitching. Poster-boy perfect: every one craved him like a vice. “Seriously, though. It’s no big deal.”

“No big deal, he says. Freaking billionaires.”

“Caaaaat.”

Have you ever cannonballed into a cold lake? The shock of an old memory is kind of like that; every neuron singing a bright hosanna: here we are. You forgot about us, but we didn’t forget about you.

Only one other person had ever said my name that way.

“Is Lin coming?” I licked the corner of a tooth.

“No comment.”

You could just about smell the cream on the lip of Phillip’s grin, though. I tried not to cringe, to wince, beset by a zoetrope of sudden emotions. I hadn’t spoken to Lin since before I checked myself into the hospital for terminal ennui, exhaustion so acute it couldn’t be sanitized with sleep, couldn’t be remedied by anything but a twist of rope tugged tight. The doctors kept me for six days and then sent me home, pockets stuffed with pills and appointments and placards advocating the commandments of safer living. I spent six months doing the work, a shut-in committed to the betterment of self, university and my study of Japanese literature, both formal and otherwise, shelved, temporarily.

When I came out, there was a wedding and a world so seamlessly closed up around the space where I stood, you’d think I was never there in the first place.

A door thumped shut and we both jumped, turned like cogs. All my grief rilled somewhere else. I swear, if that moment wasn’t magic, wasn’t everything that is right and good, nothing else in the world is allowed to call itself beautiful. It was perfect. A Hallmark commercial in freeze-frame: autumn leaves, swirling against a backdrop of beech and white cedar; god rays dripping between the boughs; Faiz and Talia emerging, arms looped together, eyes only for each other, smiling so hard that all I wanted to do was promise them that forever will always, eternally, unchangingly be just like this.

Suenomatsuyama nami mo koenamu.

My head jackknifed up. There it was. The stutter of a girl’s voice, sweet despite its coarseness, like a square of fabric worn ragged, like a sound carried on the last ragged breath of a failing record player. A hallucination. It had to be. It needed to be.

“You heard something spooky?” said Phillip.

I strong-armed a smile into place. “Yeah. There’s a headless lady in the air right there who says that she killed herself because you never called. You shouldn’t ghost people, dude. It’s bad manners.”

His joviality wicked away, his own expression tripping over old memories. “Hey. Look. If you’re still mad about—”

“It’s old news.” I shook my head. “Old and buried.”

“I’m still sorry.”

I stiffened. “You said that already.”

“I know. But that shit that I did, that wasn’t cool. You and me—I should have found a better way of ending things, and—” His hands fluttered up and fell in time with the backbeat of his confession, Phillip’s expression cragged with the guilt he’d held for years like a reliquary. This wasn’t the first time we’d had this conversation. This wasn’t even the tenth, the thirtieth.

Truth was, I hated that he still felt guilty. It wasn’t charitable but apologies didn’t exonerate the sinner, only compelled graciousness from its recipient. The words, each time they came, so repetitive that I could tune a clock to their angst, sawed through me. You can’t move forward when someone keeps dragging you back. I trapped the tip of my tongue between my teeth, bit down, and exhaled through the sting.

“Old news,” I said.

“I’m still sorry.”

“Your punishment, I guess, is dealing with bad puns forever.”

“I’d take it.” Phillip made a bassoon noise deep in his lungs, a kind of laugh, and traded his Timberlands for the pair of slippers he’d bought at a souvenir shop at the airport. It’d cost him too much, but the attendant, her lipstick game sharp as a paper cut, had thrown in her number, and Phillip always folds for wolves in girl-skin clothing. “Long as you promise you don’t spook the ghosts.”

In another life, I had been brave. Growing up where we did, back in melting-pot Malaysia, down in the tropics where the mangroves spread dense as myths, you knew to look for ghosts. Superstition was a compass: it steered your attention through thin alleys, led your eyes to crosswalks filthy with makeshift shrines, offerings and appeasements scattered by traffic. The five of us spent years in restless pilgrimage, searching for the holy dead in Kuala Lumpur. Every haunted house, every abandoned hospital, every storm drain to have clasped a body like a girl’s final prayer, we sieved through them all.

And I was always in the vanguard, torchlight in hand, eager to show the way.

“Things change.”

A breeze slouched through the decaying shoji screens: lavender, mildew, sandalwood, and rotting incense. Some of the paper panels were peeling in strips, others gnawed to the still vividly lacquered wood, but the tatami mantling the floors—

There was so much, too much of it everywhere, more than even a Heian noble’s house should hold, and all of it was pristine. Store-bought fresh even, when the centuries should have chewed the straw to mulch. The sight of it itched under my skin, like someone’d fed those small, black picnic ants through a vein, somehow; got them to spread out under the thin layer of dermis, got them to start digging.

I shuddered. It was possible that someone’d come in to renovate, maybe someone who’d decided that if the manor was going to house five idiot foreigners, they might as well make it a bit more livable. But the interior didn’t smell like it’d had people here, not for a long, long time, and smelled instead like such old buildings do: green and damp and dark and hungry, hollow as a stomach that’d forgotten what it was like to eat.

“Does someone use this as a summer house?”

Phillip shrugged. “Probably? I don’t know. My guy didn’t want to talk too much about it.”

I shook my head. “Because something about this place doesn’t add up.”

“We’re probably not the only customers in the ‘destination horror’ business,” said Phillip, grinning. “Relax.”

Faiz whistled, interrupting me. “Yeah, this is the real deal. My man, Phillip. You’re a gentleman and six quarters.”

“Was nothing.” Phillip bared a bright fierce grin at the happy couple. “Just some good old-fashioned luck and the family money put to great use.”

“You don’t ever quit about that inheritance, do you?” said Faiz, smile only as far as the spokes of his cheeks, eyes flat. He cupped an arm around Talia’s waist. “We know you’re rich, Phillip.”

“Come on, dude. That wasn’t what I was trying to say.” Arms spread, body language open as a house with no doors. You couldn’t hate Phillip for long. But Faiz was trying. “Besides, my money is your money. Brothers to the end, you know?”

Talia was taller, duskier than Faiz. Part Bengali, part Telugu. Legs like stilts, a smile like a Christmas miracle. And when she laughed, low like a note in a cello’s long throat, it was as if she had been the one to teach the world the sound. Talia laid long fingers atop the jut of Phillip’s shoulder and bowed her head, precociously regal. “Don’t fight. Both of you. Not today.”

“Who’s fighting?” Faiz had a radio voice, an easy-listening tenor just about south of primetime worthy. Nothing some hard living couldn’t fix, some good cigarettes and bad whiskey. He wasn’t much of anything except doughier than ever. Not fat—not that there was anything wrong with that—but glutinous almost, soft as good clay. Beauty and her unfinished pottery, half-molded, still slick; the tips of Faiz’s hair jutting out at the nape, dewed with sweat.

I felt an immediate guilt at the unkind observation. Faiz was my best friend and he’d done more than his share, talking Talia down from walling me out. She and I made eye contact as the boys bantered, their voices prickling like the hackles of a Doberman, short and stark, animosity panting between the niceness, and Talia’s expression congealed with dislike.

I stroked a hand over my arm and tried to keep a smile on. A muscle in Talia’s jaw went rigid as she cracked her face into a similar configuration: her smile tense, mineral, bracketed with impatience.

“I didn’t think you were actually going to come. Not after everything you had to say about the two of us.” Courtesy velveted her voice. Talia peeled from Faiz and strode across the room, closing the distance between us two inches too much. I could smell her: roses and sweet cardamom.

“You two weren’t happy,” I said, hands burrowed into my pockets, a slight backward lean to the axis of my spine. “I’m glad that you figured out your differences but at the time, you were at each other’s throats—”

Talia had almost three inches on me and levered that to her advantage, looming. “Your insistence that we break up didn’t help.”

“I didn’t insist anything.” I heard my voice constrict, the registers narrow so much, every syllable caught and was crushed together into a slurry. “I just thought—”

“You nearly cost me everything,” Talia said, still staccato in her rage.

“I had both your best interests at heart.”

“Are you sure?” Her expression shaded with pity. I glanced at the boys. “Or were you hoping to get Faiz back?”

We had dated—if you could call it that. Eight weeks, no chemistry, not even a kiss, and had we been older, our confidence less flimsy, less dependent on the perceived temperature of our reputations, we’d have known to end it sooner. Something came out of that, at least: a friendship. Guilt-bruised, gestated in the shambles of a stillborn romance. But a friendship nonetheless.

The light deepened in the house, blued where it broke into the corridors.

“I’m fucking sure of it. And Jesus, I don’t want your man,” I told her with as much detachment as I could scrounge, not wanting to sell Faiz short. Not after all this. “It’s been years since we were together and I don’t know what more you want from me. I’ve apologized. I’ve tried to make it up to you.”

Talia let a corner of her lips wither. “You could have stayed home.”

“Yeah, well.”

The sentence emptied into a surprised flutter of noises as the two guys—men, barely, and by definition rather than practice, their egos still too molten—came tumbling back from the periphery. Phillip had Faiz laughingly mounted on a shoulder, a half fireman carry with the latter’s elbow stabbed into the divot of Phillip’s collarbone. Faiz, he at first looked like he might have been grinning through the debacle, but the way his skin pulled upward from his teeth: that said different. It was a grimace, bared teeth restrained by a membrane of decorum.

“Put my husband down!” Talia fluted, reaching for her groom-to-be.

“I can handle it.” A snarling comeback without an anchor, in fact. Phillip could have kept Faiz suspended forever, but he relented as Talia curved a shoulder against him, arms raised like a supplicant. He set Faiz down and took a languid step back, thumbs hooked through his belt buckles, his grin still easy-as-you-please.

“Jackass,” said Faiz, dusting the indignity from himself.

“So tell me about this place, Phillip,” said Talia, voice billowing in volume, filling the room, the house and its dark. “Tell me this isn’t secretly Matsue Castle. Because I’ll kill myself if it is. I heard they buried a dancing girl in the walls and the castle shakes if anyone even thinks about dancing near it.”

The manor seemed to breathe in, drinking her promise. I could tell we all noticed it, all at once, but instead of hightailing it, we bent our heads like this was a baptism.

“The house might hold you to that,” I blurted before I could stop myself, and the sheer wrongness of the statement, the weird puppyish earnestness in its jump from my throat, made me cringe. A long year spent making acquaintances with the demons inside you, each new day a fresh covenant. It does things to you. More specifically, it undoes things inside you. To have to barter for the bravery to go outside, pick up the phone, spend ten minutes assured in the upward trajectory of your recovery: that the appointments are enough, that you can be enough, that one day, this will be enough to make things okay again. All those things change you.

Still, no one looked askance. If anything, the words lit something in their expression, the last light of the day etching their faces in rough shadows. Talia held my gaze, her eyes cold black water.

“Luckily,” Phillip, and stretched like a dog, long and lazy, completely unselfconscious. Scratched behind his ear, a smile crooking his lips. “This isn’t Matsue Castle.”

Faiz patted Talia’s arm. “Nah, not even Phillip could rent out a place like that.”

Phillip tried on abashment, complete with an honest-to-god aw-shucks toe scuffing, but it didn’t work. At this point, he’d been homecoming king, class valedictorian, debate captain, chess wunderkind, every type of impressive a boy could hope to be, king of kings in a palace of princes. Even when they try, guys like him can’t do self-effacing.

But they can be good sports.

“This is better.” I rolled my luggage up against a pillar, slouched carefully against the wood. Despite everything, I was warming to their enthusiasm, partially because it was so much easier to just go along with it, less lonely too. Media’s all about the gospel of the lone wolf, but the truth is we’re all just sheep.

“But what is this exactly?” said Faiz, ever meticulous when love was a mandrel in his deliberations. His fingers bangled Talia’s wrist and his smile creased from worry.

“Well.” Phillip gutted the word, unstrung it over twenty seconds. “My guy wouldn’t give me a name. He said he didn’t want anything on record in case—”

“Could have just told you over the phone,” said Faiz.

Phillip tapped the side of a finger to his temple. “Didn’t want it to be a ‘he said, they said’ thing either. He was a stickler for the rules.”

“I guess it is cultural,” said Faiz, full of knowing. His mother was Japanese, small-framed and smileless. “Makes sense.”

“We have a permit for this, though. Right?” said Talia, a wobble in her gilded prep-school inflections.

“Yeah. We do. Don’t worry about that.” Phillip palmed the back of his neck. “Well. Sort of. We have a permit allowing us to access the land here. The mansion’s sort of… collateral benefit.”

“Okay. So, we don’t have a name,” began Faiz, counting sins on his fingers. “We don’t actually have a permit to be here. But we have booze, food, sleeping bags, a youthful compulsion to do stupid shit—”

“And a hunger for a good ghost story,” said Talia. The late light did beautiful things to her skin, burnished her in gold. “What is the scoop on this mansion?”

“I don’t know,” Phillip said, the singsong timbre of his voice familiar, the sound of it like a coyote lying about where he’d left the sun. “But rumour has it that this was once supposed to be the site of a beautiful wedding. Unfortunately, the groom never showed up. He died along the way.”

“If you die,” said Talia, pinching a curd of Faiz’s waist between her fingers, “I’m gonna marry Phillip instead. Just so you know.”

Phillip smiled at the proclamation like he’d heard it ten times before from ten thousand other women, knew every syllable was meant, would already be true if it weren’t for fraternal bonds, and I was the only one who saw how Faiz’s answering smile wouldn’t climb to his eyes.

“I don’t think you’re allowed to marry your priest,” Faiz said, easy as anything. “But if you had to get a replacement, I’d rather you pick Cat.”

“Ugh,” I said. “Not my type.”

“I’d rather die an old maid. No offense,” said Talia.

“None taken.”

“Anyway,” said Phillip with a clearing of his throat. “The bride took her abandonment in stride and told her wedding guests to bury her in the foundation of the house.”

“Alive?” I whispered. I thought of a girl holding both hands to her mouth, swallowing air and then dirt, her hair and the hems of her wedding dress becoming heavier with every shovel’s worth of soil to come down.

“Alive,” said Phillip. “She said she had promised to wait for him and she would. She’d keep the house standing until his ghost finally came home.”

Silence placed itself to rest along the house and upon our tongues.

“And every year after that, they buried a new girl in the walls,” said Phillip.

“Why,” started Faiz, startling somehow at this revelation, “the fuck would they do that?”

“Because it gets lonely down in the dirt,” Phillip continued, while I held my tongue to the steeple of my mouth. “Why do you think there are so many stories of ghosts trying to get people to kill themselves? Because they miss having someone there, someone warm. It doesn’t matter how many corpses are lying in the soil with them. It’s not the same. The dead miss the sun. It’s dark down there.”

“That’s—” Talia walked a hand along Faiz’s arm, a gesture that said look, you have to understand that this belongs to me. Her eyes found mine, liquid and unkind. In that instant, I wanted badly to tell her again that the past was so sepulchered in poor choices, you couldn’t get Faiz and me back together for bourbon enough to brine New Orleans. But that wasn’t the point. “—That’s pretty fucking metal.”

“We’ll be fine. Freshly certified man of the cloth right here.” Phillip pounded his sternum with a fist, laughing, and Talia immediately kissed Faiz in answer. He took her knuckles to his mouth, grazed each of them with his lips in turn. I stared at the skins of woven straw thatching the floors, shuddered despite myself. I was abruptly dumbstruck by a profound curiosity.

How many dead and dismembered women laid folded in these walls and under these floors, in the rafters that ribbed the ceiling and along those broad steps, barely visible in the murk?

Tradition insists the offerings be buried alive, able to breathe and bargain through the process, their funerary garments debased by shit, piss, and whatever other fluids we extrude on the cusp of death. I couldn’t shake the idea of an eminently practical family, one that understood that bone won’t rot where wood might, ordering their workers to stack girls like bricks. Arms here, legs there, a vein of skulls wefted into the manor’s framing, insurance against a time when traditional architecture might fail. Might as well. They were here for the long haul. One day, these doors would open and wedding guests would pour through and there would be a marriage, come the cataclysm or modern civilization.

The house would wait forever until it happened.

One girl each year. Two hundred and six bones times a thousand years. More than enough calcium to keep this house standing until the stars ate themselves clean, picked the sinew from their own shining bones.

All for one girl as she waited and waited.

Alone in the dirt and the dark.

“Cat?”

I blinked free of my fugue, fingers clenched around my wrist. “I’m okay.”

“You sure?” Phillip cocked a worried look, hair haloed by a slant of owl-light. “You don’t look like you’re fine. Is it—”

“Leave it,” Faiz said softly. The joy’d gone out of his expression, replaced by concern, a twitch of protective anger that carried to his teeth, his lips peeling back. I wagged my head, smoothed out a smile. It’s fine. Everything’s fine. “Cat knows we’re here if she needs us.”

The look on my face must have been a sight to see because Phillip flinched and ducked out of the room, mumbling about mistakes, cheeks blotching. I ran through my to-do list thrice, counted out chores, precautions, a thousand trivialities, until order restored itself by way of monotony. I glanced over, breathing easy again, to see Faiz and Talia bent together like congregants, a steeple made of their bodies, foreheads touching. It was impossible to miss the cue.

Exit, stage anywhere.

So, I followed the shutter-pop of Phillip’s new camera to where he stood in an antechamber, painted by the evening penumbra, dusk colors: gold and pink. A moting of dust spiraled in the damp air, glinting palely where particles caught in the cooling sun. At some point, the roof here had fissured, letting the weather slop through. The flooring underneath was rotten, green where the mould and ferns and whorls of thick moss had taken root in the mulch.

“Sorry.”

I shrugged. There were wildflowers by the lungful, swelling at Phillip’s feet. “It’s fine.”

His eyebrows went up.

A bird shrilled its laughter. Through the wound in the roof, I saw a flash of ambergris and tanzanite, the teal of a feathered throat. Phillip stretched, a Rembrandt in high-definition. “Cat—”

“You were just worried about a friend. It happens.”

“Yeah, but—”

“I’m not going to throw myself off a building because you were trying to be nice. That’s not how it works.” I swallowed.

“Okay. Just… tell me what you need, all right? I don’t—I don’t always know the right things to say. I mean, I’m okay at some things, but—”

Like women, I thought. Like being a star, being loved, being hungered for. Phillip excelled at inciting want, particularly the kind that tottered on the border of worship. Small wonder he was so inept at compassion sometimes. Every religion is a one-way relationship.

To our right, a half-opened fusuma—the opaque panel stood floor to ceiling, slid noiselessly on its rail when I pushed—that opened into a garden: a neat square of emerald bracketed by verandahs, an algae-swallowed pool at its heart. The foliage crawled with red higanbana, dead men’s flowers.

I ran my fingers through my hair. I was suddenly, irrevocably exhausted, and the thought of having to exorcise Phillip’s guilt again, to assure him that he wasn’t a bad man, nauseated me. In lieu of comfort, I groped for inanities.

“When did you date Talia? Was it after or while we were seeing each other?”

“Cat?” A laugh startled from him.

“I don’t mean that as an accusation. It doesn’t matter. I was just wondering.” I stroked a finger along the bamboo lattice, came out with dust, decomposing plant material, an oiliness that I couldn’t place.

“About a month after. But we weren’t exclusive or anything.”

“You never did like the exclusive thing, no.”

“It’s not that.” So much sincerity in those gold-blue eyes, crowns of honey around black pupils. “It’s just we were kids. We’re still kids. These relationships won’t last us into adulthood. Most of them won’t. Talia and Faiz, that’s something else. Anyway. When I’m older, I’ll settle down. But these are the best years of my life and I don’t want to waste them shackled to a person I won’t like at thirty.”

His gaze became pleading.

“You understand, right?” said Phillip, yearning for affirmation.

“I’m just wondering if Faiz knows you two were together.”

He stilled.

“That’s on Talia to tell him. Not me.” I considered my next words.

“In case he doesn’t know, I feel like you should make it a point to pretend that you two weren’t ever an item.”

Guileless, the reply: “Why?”

I thought of Faiz and his teeth, bared and blunt and bitter. “Faiz might not like suddenly finding out that you slept with his fiancée.”

“He’s an adult. And male. He’s not going to care about someone’s sexual history.”

“Better safe than sorry, Phillip.” I paused. “Also, fuck you. Faiz is an adult who can make his own decisions, but you’re a kid who shouldn’t commit yet?”

“Hey, people mature at different speeds.”

“Jesus. Fine. Just make sure you don’t let Faiz know you used to sleep with his wife-to-be.”

“Okay.” Phillip put his hand out, his blunt nails grazing a fold of my shirt. “For you.”

I wove my shoulder away.

“Don’t do that.” Something below the crossbeams of my lowest ribs clenched as I absorbed him, the chiaroscuro of his face in silhouette, his faultless smile. Nothing ever said no to those cheekbones. “You know you’re supposed to ask.”

“Sorry, I forgot.” Glib as the first word out of a babe’s milk-wet mouth, one shoulder raised then dropped.

My gaze drifted, moved until it came to rest on the fusuma. There were images of marketplaces teeming with black-lipped housewives, raccoons darting between—

I squinted. No, not raccoons. Tanuki, with their scrotums dragging behind them. Someone’d even painted the fine hairs, had made it a point to emphasize how the testes sat in their gunny sacks of tanned skin. Somehow, the profanity of the art repulsed me less than the undergrowth in which Phillip stood. The ferns grew knee-high, curled against his calves like vegetal cats.

“So, how many ghosts do you think we’re going to find?” Phillip said, warming to the thought of small talk, his grin like a politician’s smile beaming up from the cover of GQ, only better because it was actually sincere, larger than life yet still intrinsically boy next door. “At least one.” I thought about corpses. I thought about how many girls were buried beneath us, foreheads together, bodies fused in a cat’s cradle of curled legs and clutching arms.

“Yeah. She’s probably like the Queen of the Damned or something. I wonder what she’d look like.” He undulated his hands through the air, molding his palms around the voluptuous rise and dip of an imaginary silhouette. “Bet she’s hot.”

A portraiture of the deceased—the owner of that voice—rose into focus in my mind’s eye: a round face, wide at the cordillera of her cheekbones but otherwise gaunt, the flesh whittled by hunger and worms, her complexion waxen. Hair waterfalling ragged and black, still impaled in places by sharp golden pins.

“I don’t think you can be hot after so many years dead.”

“Have some imagination. Sure, the corporeal body might have suffered from decomposition. But her spiritual manifestation is probably something else.”

“You’re crass, Phillip.” My laugh sounded wet, thick, false, forced. But Phillip didn’t notice, grinning wide. I couldn’t stop thinking about what might have been under his feet.

“Just a hot-blooded male,” he confessed. “Doing what hot-blooded males do.”

“Cute.” The edge of a lip went up further than demure. “Promise me you’ll rein it in.”

“I promise I’ll try.” He fisted a hand and placed it over his heart, an admiral’s salute, spine and shoulders lancing straight. That grin again, that cocksure state-funded presidential candidate smirk.

“Talk to the hand.” I threw a raised palm in his direction and looked back to the fusuma. It wasn’t just tanuki on exhibit. There were other yokai. It was all yokai, a veritable parade: kitsune in elaborate tomesode, tails curling with questions. Ningyo crawling from the jeweled sea. Kappa and towering oni, negotiating for baskets heaped with cucumbers. Everywhere, every last brush-painted face in sight. Even the housewives: some with eyes, some only with lips, some with gaping smiles sliced into place. Every last one of them. All fucking yokai.

“Just trying to make you laugh, Cat. That’s all.”

“That’s what he said.”

He swept his fringe from his eyes and palmed his chest with both hands, expression become grotesque with false despair. “You wound me.”

“Your ego wounds you. I was just its instrument.”

And he laughed then. Like it didn’t matter, like it couldn’t matter, not for him, not ever, not when so much of the world waited, eager, to tithe him everything for a kiss. Phillip wouldn’t pauper himself with a grudge, not with the blessed largesse of his straight, white, rich-boy life.

“You’re good people, Cat. You know that, right? And good people deserve happiness.”

“I think that’s overstating things,” I told him with a half-smile for a tip. However tedious the best wishes, I couldn’t fault his intent. More than anything else, I was tired. Tired of being unhappy, and even more tired of feeling sorry for the fact that I was unhappy. It was easier to agree than it was to argue, what with the immovable object that was Phillip’s faith in his worldview. “But I appreciate the sentiment.”

Suenomatsuyama nami mo koenamu.

A whisper, so quiet the cerebellum wouldn’t acknowledge its receipt. The words were drowned by the reverb of Faiz’s voice calling, an afterimage, an impression of teeth on skin. We exited the room, the future falling into place behind us. Like a wedding veil, a mourning caul. Like froth on the lip of a bride drowning on soil.

Excerpted from Nothing But Blackened Teeth, copyright © 2021 by Cassandra Khaw.